By Dr Mamtamayi Priyadarshini

A balanced reflection from a pro–non-GM advocacy perspective

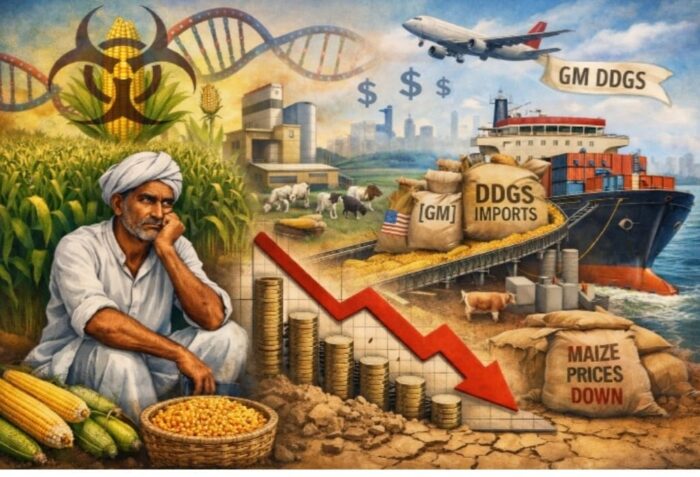

India’s recent decision to allow concessional imports of dried distillers’ grains with solubles (DDGS) under the interim trade framework with the United States has sparked discussion across agricultural and feed industry circles. The government has capped imports at 500,000 tonnes — approximately 1% of domestic consumption — and positioned the measure as a calibrated step aimed at easing feed costs for poultry, dairy and aquaculture sectors.

At first glance, the policy appears limited in scope. Yet agricultural markets are shaped not only by volumes, but also by signals. Even relatively modest trade concessions can influence price expectations, bargaining power and rural income structures in ways that extend beyond their numerical share.

Understanding DDGS in the Broader Context

DDGS is a protein-rich by-product of maize-based ethanol production. In the United States — where most maize cultivation is genetically modified — DDGS is produced at industrial scale and widely used as animal feed. For India, the question is not merely about substituting one feed ingredient for another. It is about how such imports may interact with domestic maize markets, farmer incomes and India’s precautionary approach toward genetically modified crops.

Policymakers have emphasized the potential for cost relief to livestock industries. That objective is understandable, particularly in sectors that directly influence food prices and nutritional security. At the same time, it is worth examining how the distribution of benefits and risks may unfold across different stakeholders.

The Subtle Dynamics of Market Signals

On paper, a 1% import quota seems modest. In practice, however, imports can establish a reference price in the market. Large feed manufacturers and integrated poultry companies now have an additional sourcing option. This potentially strengthens their negotiating leverage when purchasing domestic maize or soybean meal.

In commodity markets, perception can influence pricing as much as supply volumes do. If buyers can point to lower-cost imported DDGS, domestic suppliers may feel pressure to align prices accordingly. Even before significant quantities enter the supply chain, the signalling effect alone can shape market sentiment.

For India’s maize farmers — many of whom operate on thin margins — these shifts can matter. Rising input costs for hybrid seeds, fertilizers, irrigation and transportation already weigh heavily. Limited storage infrastructure often compels farmers to sell soon after harvest, reducing their ability to wait for favorable price cycles. In such conditions, even a 5–10% softening in farmgate prices can meaningfully affect annual household income.

Distribution of Gains and Pressures

The potential advantages of DDGS imports are likely to accrue primarily to large feed integrators and industrial processors, who may benefit from diversified sourcing and improved margins. Whether such cost efficiencies translate into lower consumer prices for poultry, dairy or aquaculture products remains uncertain and depends on value-chain dynamics.

Conversely, small and marginal maize farmers could bear a disproportionate share of adjustment pressures if local demand weakens. Domestic traders, regional feed processors and associated rural service providers — transporters, warehouse operators, commission agents and labourers — form part of a broader ecosystem linked to maize cultivation. Gradual shifts in sourcing patterns could affect this interconnected rural economy.

These concerns do not imply that imports will inevitably destabilize markets. Rather, they underscore the importance of monitoring and policy responsiveness.

The Regulatory and Precedent Dimension

India has historically adopted a cautious approach toward commercial genetically modified food crops. While DDGS is a processed residue and not a seed, its origin from predominantly GM maize introduces a regulatory nuance. Some stakeholders view this development as a potential shift in precedent, even if indirect.

Agricultural policy is shaped not only by scientific assessments but also by public trust and consistency. Transparent biosafety evaluation, clear documentation of origin and open public communication can help maintain confidence. Once trade pathways are established, they often evolve, making early safeguards particularly important.

India also occupies a distinct position in certain export markets as a supplier of non-GM agricultural products. Preserving clarity around this identity may carry long-term strategic value. In that sense, the DDGS decision intersects with broader considerations of trade positioning and agricultural branding.

Balancing Feed Efficiency and Farmer Welfare

The needs of the poultry, dairy and aquaculture sectors are legitimate. Feed efficiency contributes to food affordability and nutritional security. However, agricultural policy works best when it carefully balances industrial competitiveness with farmer welfare.

If concessional imports proceed, they could be accompanied by defined safeguards — such as mandatory testing of consignments, full chain-of-custody documentation, disclosure requirements for feed mills and periodic policy reviews involving farmer representation. A clearly defined trial period with transparent evaluation metrics may also enhance accountability.

Parallel investment in domestic capacity offers another constructive pathway. Strengthening India’s ethanol industry and encouraging indigenous production of feed co-products would allow the country to meet rising feed demand while retaining value addition within domestic supply chains. Supporting innovation in non-GM feed alternatives could further reinforce resilience.

A Question of Calibration

The DDGS import decision may appear numerically small, yet its economic and symbolic dimensions are meaningful. Trade engagement is a natural component of a modern economy. The broader question is how such engagement is calibrated to protect those who may face adjustment costs.

Maize farmers are central participants in India’s agricultural landscape. Ensuring that short-term feed cost considerations do not unintentionally weaken long-term farmer resilience is a shared responsibility. Agricultural policy, ultimately, is measured not only in tonnes and percentages, but in the stability of livelihoods and the confidence of rural communities.

About the author: Dr. Mamtamayi Priyadarshini is an environmentalist, social worker and author of Maize Mandate. She has written extensively on agricultural sustainability, seed sovereignty and the intersections of food and fuel policy in India.